Our Spotlights

Read expert perspectives on current news and events and connect with leading University of Florida experts to learn more.

Florida renters struggle with housing costs, new statewide report finds

Nearly 905,000 low-income renter households in Florida are struggling to afford their housing costs, according to the 2025 Statewide Rental Market Study, released by the University of Florida’s Shimberg Center for Housing Studies. Prepared for Florida Housing Finance Corporation, the report provides a comprehensive look at the state’s rental housing conditions and is used to guide funding decisions for Florida Housing’s multifamily programs, including the State Apartment Incentive Loan (SAIL) program. “Florida’s strong population growth has collided with limited housing supply, pushing rents beyond what many families can afford,” said Anne Ray, manager of the Florida Housing Data Clearinghouse at the Shimberg Center. “This report helps policymakers and housing providers target resources where the need is most acute — including communities that are experiencing the fastest growth and the greatest affordability gaps.” Key findings from the 2025 study include: A growing affordability gap: An estimated 904,635 renter households earning below 60% of their area median income (AMI) are cost burdened, paying more than 40% of their income toward rent. These households are spread across the state, with 64% in Florida's nine most populous counties, 33% in mid-sized counties and 3% in small, rural counties. Surging population and higher rent and housing costs: Between 2019 and 2023, Florida added more than 1 million households — nearly 195,000 of them renters — driven by in-migration from states like New York, Illinois and California. Despite the addition of more than 240,000 multifamily units, median rent soared nearly $500 per month, from $1,238 to $1,719. After years of growth, Florida's older renter population is holding steady: Renters age 55 and older represent 39% of cost burdened households, up from 29% in 2010 but similar to 2022 numbers. Most renters are working: 79% of renter households include at least one employed adult, compared to 67% of owner households. Most non-working renters are seniors or people with disabilities. Homelessness is on the rise: The report estimates 29,848 individuals and 44,234 families are without stable housing, up from 2022, as hurricanes and tight markets contribute to displacement. Assisted housing provides an alternative to high-cost private market rentals: Developments funded by Florida Housing, HUD, USDA and local housing finance authorities provide over 314,000 affordable rental units statewide. Future risks to affordable housing stock: More than 33,000 publicly assisted units may lose affordability protections by 2034 unless renewed. Evalu ating affordable housing in Florida “State- and federally-assisted rental housing developments are essential to providing stable, affordable homes for Florida’s workforce, seniors, and people with special needs,” Ray said. “Florida Housing Finance Corporation’s programs make up a significant portion of this housing, and our study helps ensure those resources are directed where they’re needed most. Preserving these developments — and expanding them — is critical to keeping pace with Florida’s growing population and maintaining affordability.” Since 2001, the Shimberg Center has produced the Rental Market Study every three years to inform strategic investments in affordable housing across Florida. The study evaluates needs across regions and among key populations including seniors, people with disabilities, farmworkers and others. The Rental Market Study and the Florida Housing Data Clearinghouse are part of a 25-year partnership between the Shimberg Center and Florida Housing Finance Corporation to support data-driven housing policy and planning.

February 26, 2026

3 min

Labubu success demonstrates the benefits of the ‘blind box’ business strategy

Labubu dolls have taken the world by storm. The viral collectable keychains that feature plush monster-like figurines, sold by the Chinese company Pop Mart, have been compared to other toys like Beanie Babies or the more recent Sonny Angels. Labubus come in a variety of colors and outfits, and they are sold in “blind boxes” — so customers never know which collectibles they will get when they buy them. The meteoric ascent of these toys raises the question: What exactly is the appeal of Labubus? According to Tianxin Zou, Ph.D., an assistant professor of marketing in the University of Florida Warrington College of Business, there are a few reasons behind Pop Mart’s success. “It’s a little bit like buying a lottery ticket,” Zou said about the blind box concept. “The uncertainty is giving another layer of enjoyment.” Zou compares the psychological experience of blind boxes to gambling, stating that some customers buy hundreds of boxes for the chance at winning big. Customers aren’t just buying the products; they’re buying the experience. Each Labubu release features 12 figurine designs, as well as a much rarer secret design, so customers are enticed by the possibility of getting that one rare doll. This can also come with monetary value, as Labubus have been resold for thousands of dollars on platforms like eBay. Recently, a first-generation Labubu toy sold for $150,000 in a Labubu-specific auction. The unboxing experience can also trigger social interaction. People often film themselves unboxing the products and posting the experiences online for millions to see, or they gather in person to open boxes with their friends. This brings people together, forming a sense of community and identity around Labubu ownership. “Unboxing the blind box together can become a joyful event,” Zou said. “It makes it so Labubu has a social value and can help form friendships.” The rarity of certain designs is also a key factor in the social aspect of Labubus. Within these communities, especially online, owning rare designs can become a form of social capital. This has contributed to the rise of “Lafufus,” or fake Labubu dolls sold by retailers separate from Pop Mart. The craze has become less about the item itself and more about what it represents socially. Even if a keychain is fake, it still shows that the owner is socially in the know. Pop Mart also aligns itself with well-known franchises, such as Star Wars and Marvel, for branded blind box designs. And celebrity interest has helped the popularity of Labubus skyrocket. The toy first gained momentum after it was seen on the bag of Lisa, a member of the K-pop group Blackpink. Since then, Labubus have been spotted on the bags and belt loops of public figures ranging from Rihanna to Tom Brady. Zou explains that this furthers the social impact of the toys, as people aim to replicate celebrities’ style. “This collaboration with celebrities gives Pop Mart synergy, which gives it this stronger social effect,” Zou said. While the success of Labubus may seem spontaneous, it is actually the result of highly strategic business strategies. However, other retailers are catching on, providing competition for Pop Mart as more companies enter the blind box game. The retailer also faces new challenges, with countries like China and Singapore creating regulations for the sale of blind boxes, especially to children. But for now, the monsters continue to dominate the market, giving the company time to formulate new strategies. And because the company’s strength lies in its research and planning, it likely will not be going into its next phase blind.

February 23, 2026

3 min

Beyond the field: New research highlights how NIL is reshaping college athlete identity

In an era of name, image and likeness, or NIL, many college athletes are thinking differently about who they are — seeing themselves not just as competitors or students, but also as influencers with distinct voices and causes, according to a new study from the University of Florida. Molly Harry, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Sport Management at the UF College of Health and Human Performance, surveyed 200 athletes from 21 Power Four universities to better understand how NIL, which refers to the rights of college athletes to earn money through endorsements, sponsorships, social media promotions and other commercial opportunities, has impacted the way athletes perceive their roles and identities. “Historically, we’ve viewed them (college athletes) through the lens of athletics or academics, but they’re daughters, brothers, role models, and increasingly, they’re now cultivating public personas and marketing skills.” —Molly Harry, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Sport Management The findings, published Friday in the Sociology of Sport Journal, reveal a growing recognition among athletes that they are more than the two-dimensional “student-athlete” model that is traditionally used in research and policy. “With the shift in NIL policies, athletes are starting to develop roles and identities related to that of the influencer,” Harry said. “Historically, we’ve viewed them through the lens of athletics or academics, but they’re daughters, brothers, role models, and increasingly, they’re now cultivating public personas and marketing skills.” Through survey responses across seven major sports — football, baseball, men’s and women’s basketball, gymnastics, volleyball and softball — Harry and UF doctoral student Hannah Kloetzer examined athletes' engagement with NIL opportunities, as well as the personal sacrifices they made to pursue them. They found that many athletes now view NIL as a platform to promote causes they care about, build connections with their communities and explore career pathways after college. One softball player described the value of NIL in a way that highlights the broader impact: “It’s been great to feel seen and have your hard work in a sport help in other parts of life. It’s really nice to use NIL on a resume as marketing experience.” Athletes surveyed said they found deals not just with big-name brands, but more often with local businesses like restaurants, boutiques and community partners. This entrepreneurial approach often required initiative and personal outreach, something many athletes had to learn on their own. “Some athletes told us they felt lost when trying to navigate NIL,” Harry said. “Others shared how they reached out to local businesses or organized their own camps.” One particularly striking finding, Harry said, was that some athletes were making athletic sacrifices — like spending less time training — to pursue NIL work, a shift that underscores the importance of these opportunities. Harry stressed that while no one reported skipping practices, athletes did acknowledge shifting their priorities to make room for NIL-related endeavors. “If you’re willing to give up something in your athletic routine, that speaks volumes about how central NIL — and influencer identities — could become for some athletes,” she said. Another key insight: football players of color from low socioeconomic backgrounds were most likely to self-identify as influencers. This emerging pattern stands in contrast to perceived broader trends in the social media world. “That was one of the most fascinating takeaways,” Harry said. “We have this unique subset of influencers — college football athletes — that are starting to enter this space.” Harry’s research builds on a growing conversation in the academic community about the evolving identity of college athletes. A few conceptual pieces have previously proposed the idea of a “student-athlete-influencer,” but Harry’s team is one of the first to gather empirical data to back it up. This new perspective has broad implications for how universities and organizations like the NCAA support college athletes, both during their playing years and as they prepare for life after sport. “As fans, we often see athletes as commodities on the field,” Harry said. “But they’re humans first, and they’re starting to recognize their own value and tap into their potential beyond the playing field.” In addition to academic and athletic support, Harry believes universities should invest in more targeted resources tailored to influencer pressures, like mentorship opportunities and training that goes beyond basic social media etiquette. “Athletes who take on influencer roles may deal with unique stressors, whether it’s comparing engagement numbers or coping with public scrutiny,” she said. “It would be valuable to provide opportunities where athlete-influencers can support each other, share strategies and protect their mental health.” A football player who participated in the study summed up the broader potential of NIL: “I’m very appreciative of NIL opportunities and the ability to continue to grow my camp and greater brand outside of my football program.” Looking ahead, Harry plans to explore this evolving identity through more qualitative research, with a focus on what it truly means to be an “influencer” in the context of college athletics. “Athletes are more than football players. They are more than swimmers,” she said. “They are people who we walk with on our college campuses, and they are people who bring value to our society in a host of ways.”

February 22, 2026

4 min

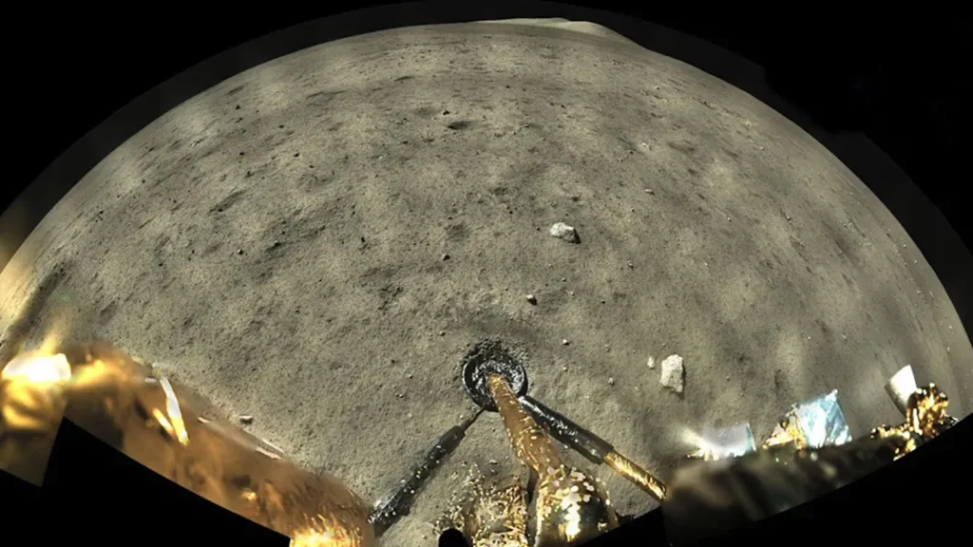

Young magmas on the moon came from much shallower depths than previously thought, new study finds

New research on the rocks collected by China's Chang'e 5 mission is rewriting our understanding of how the moon cooled. Stephen Elardo, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Geological Sciences with the University of Florida, has found that lava on the near side of the moon likely came from a much shallower depth than previously thought, contradicting previous theories on how the moon produced lavas through time. These samples of basalt, an igneous rock made up of rapidly cooled lava, were collected from the near side of the moon by the Chang’e 5 mission and are the youngest samples collected on any lunar mission, making them an invaluable resource for those studying the geological history of the moon. In order to get an estimate of how deep within the moon the Chang’e 5 lava came from, the team conducted high-pressure and high-temperature experiments on a synthetic lava with an identical composition. Previous work from Chinese scientists has determined that the lava erupted about 2 billion years ago and remote sensing from orbit has showed it erupted in an area with very high abundances of potassium, thorium and uranium on the surface, all of which are radioactive and produce heat. Scientists believe that, in large amounts, these elements generate enough heat to keep the moon hot near the surface, slowing the cooling process over time. “Using our experimental results and thermal evolution calculations, we put together a simple model showing that an enrichment in radioactive elements would have kept the Moon's upper mantle hundreds of degrees hotter than it would have been otherwise, even at 2 billion years ago,” explained Elardo. These findings contradict the previous theory that the temperature of the moon’s outer portions was too low to support melting of the shallow interior by that time and may challenge the hypothesis about how the moon cooled. Prior to this study, the generally-accepted theory was that the moon cooled from the top down. It was presumed that the mantle closer to the surface cooled first as the surface of the moon gradually lost heat to space, and that younger lavas like the one collected by Chang’e 5 must have come from the deep mantle where the moon would still be hot. This theory was backed by data from seismometers placed during the Apollo moon landings, but these findings suggest that there were still pockets of shallow mantle hot enough to partially melt even late into the moon’s cooling process. “Lunar magmatism, which is the record of volcanic activity on the moon, gives us a direct window into the composition of the Moon's mantle, which is where magmas ultimately come from,” said Elardo. “We don't have any direct samples of the Moon's mantle like we do for Earth, so our window into the composition of the mantle comes indirectly from its lavas.” Establishing a detailed timeline of the moon’s evolution represents a critical step towards understanding how other celestial bodies form and grow. Processes like cooling and geological layer formation are key steps in the “life cycles” of other moons and small planets. As our closest neighbor in the solar system, the moon offers us our best chance of learning about these processes. “My hope is that this study will lead to more work in lunar geodynamics, which is a field that uses complex computer simulations to model how planetary interiors move, flow, and cool through time,” said Elardo. “This is an area, at least for the moon, where there's a lot of uncertainty, and my hope is that this study helps to give that community another important data point for future models.”

February 18, 2026

3 min

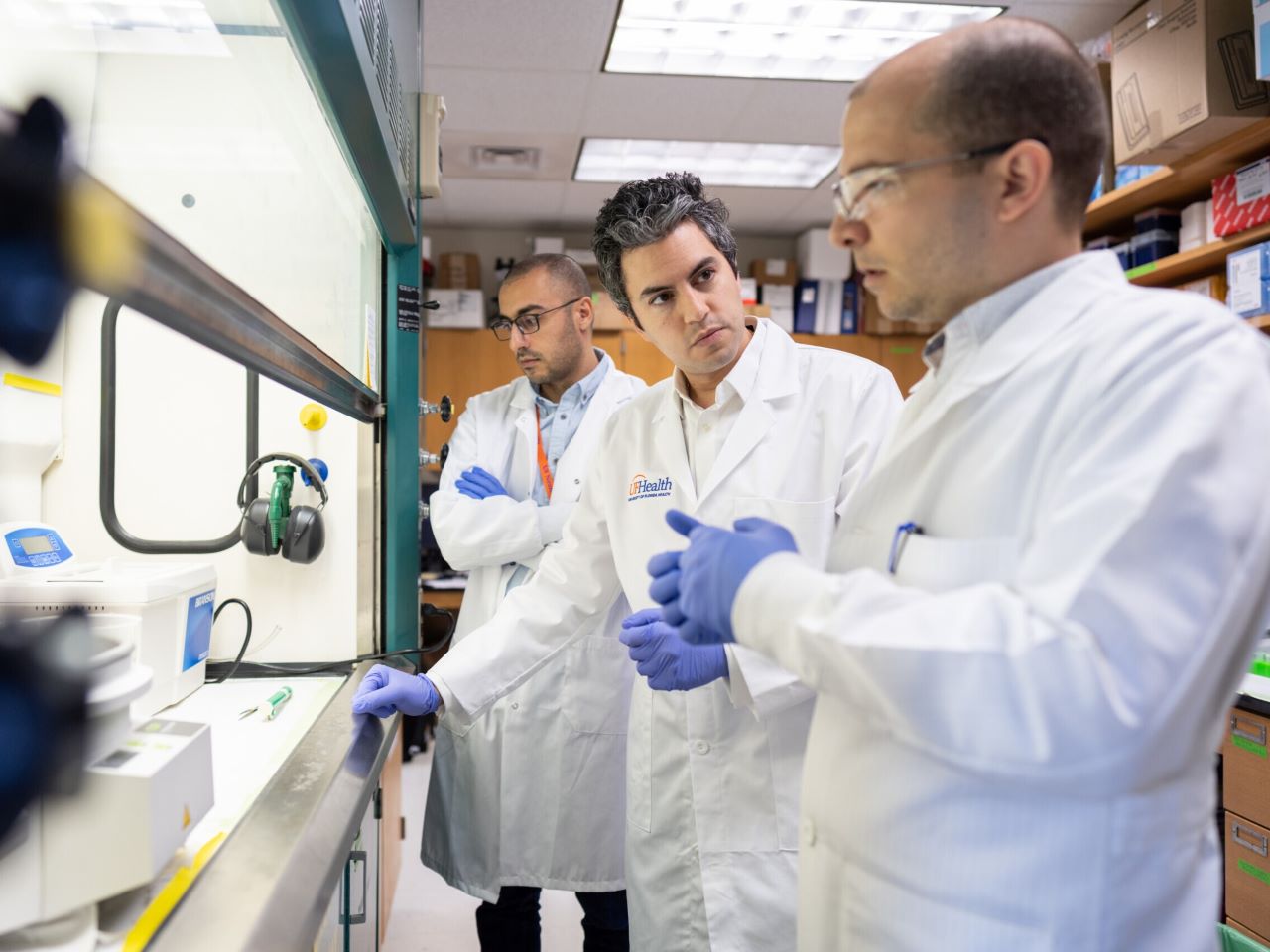

Surprising finding could pave way for universal cancer vaccine

An experimental mRNA vaccine boosted the tumor-fighting effects of immunotherapy in a mouse-model study, bringing researchers one step closer to their goal of developing a universal vaccine to “wake up” the immune system against cancer. Published today in Nature Biomedical Engineering, the University of Florida study showed that like a one-two punch, pairing the test vaccine with common anticancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors triggered a strong antitumor response in laboratory mice. A surprising element, researchers said, was that they achieved the promising results not by attacking a specific target protein expressed in the tumor, but by simply revving up the immune system — spurring it to respond as if fighting a virus. They did this by stimulating the expression of a protein called PD-L1 inside of tumors, making them more receptive to treatment. The research was supported by multiple federal agencies and foundations, including the National Institutes of Health. Senior author Elias Sayour, M.D., Ph.D., a UF Health pediatric oncologist and the Stop Children's Cancer/Bonnie R. Freeman Professor for Pediatric Oncology Research, said the results reveal a potential future treatment path — an alternative to surgery, radiation and chemotherapy — with broad implications for battling many types of treatment-resistant tumors. “This paper describes a very unexpected and exciting observation: that even a vaccine not specific to any particular tumor or virus — so long as it is an mRNA vaccine — could lead to tumor-specific effects,” said Sayour, principal investigator at the RNA Engineering Laboratory within UF’s Preston A. Wells Jr. Center for Brain Tumor Therapy. “This finding is a proof of concept that these vaccines potentially could be commercialized as universal cancer vaccines to sensitize the immune system against a patient’s individual tumor,” said Sayour, a McKnight Brain Institute investigator and co-leader of a program in immuno-oncology and microbiome research. Until now, there have been two main ideas in cancer-vaccine development: To find a specific target expressed in many people with cancer, or to tailor a vaccine that is specific to targets expressed within a patient's own cancer. “This study suggests a third emerging paradigm,” said Duane Mitchell, M.D., Ph.D., a co-author of the paper. “What we found is by using a vaccine designed not to target cancer specifically but rather to stimulate a strong immunologic response, we could elicit a very strong anticancer reaction. And so this has significant potential to be broadly used across cancer patients — even possibly leading us to an off-the-shelf cancer vaccine.” For more than eight years, Sayour has pioneered high-tech anticancer vaccines by combining lipid nanoparticles and mRNA. Short for messenger RNA, mRNA is found inside every cell — including tumor cells — and serves as a blueprint for protein production. This new study builds upon a breakthrough last year by Sayour’s lab: In a first-ever human clinical trial, an mRNA vaccine quickly reprogrammed the immune system to attack glioblastoma, an aggressive brain tumor with a dismal prognosis. Among the most impressive findings in the four-patient trial was how quickly the new method — which used a “specific” or personalized vaccine made using a patient’s own tumor cells — spurred a vigorous immune-system response to reject the tumor. In the latest study, Sayour’s research team adapted their technology to test a “generalized” mRNA vaccine — meaning it was not aimed at a specific virus or mutated cells of cancer but engineered simply to prompt a strong immune system response. The mRNA formulation was made similarly to the COVID-19 vaccines, rooted in similar technology, but wasn’t aimed directly at the well-known spike protein of COVID. In mouse models of melanoma, the team saw promising results in normally treatment-resistant tumors when combining the mRNA formulation with a common immunotherapy drug called a PD-1 inhibitor, a type of monoclonal antibody that attempts to “educate” the immune system that a tumor is foreign, said Sayour, a professor in UF’s Lillian S. Wells Department of Neurosurgery and the Department of Pediatrics in the UF College of Medicine. Taking the research a step further, in mouse models of skin, bone and brain cancers, the investigators found beneficial effects when testing a different mRNA formulation as a solo treatment. In some models, the tumors were eliminated entirely. Sayour and colleagues observed that using an mRNA vaccine to activate immune responses seemingly unrelated to cancer could prompt T cells that weren’t working before to actually multiply and kill the cancer if the response spurred by the vaccine is strong enough. Taken together, the study’s implications are striking, said Mitchell, who directs the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute and co-directs UF’s Preston A. Wells Jr. Center for Brain Tumor Therapy. “It could potentially be a universal way of waking up a patient’s own immune response to cancer,” Mitchell said. “And that would be profound if generalizable to human studies.” The results, he said, show potential for a universal cancer vaccine that could activate the immune system and prime it to work in tandem with checkpoint inhibitor drugs to seize upon cancer — or in some cases, even work on its own to kill cancer. Now, the research team is working to improve current formulations and move to human clinical trials as rapidly as possible. While the experimental mRNA vaccine at this point is in early preclinical testing — in mice not humans — information about available nonrelated human clinical trials at UF Health can be viewed here.

February 17, 2026

4 min

Psychologists introduce third path to a ‘good life’ — one full of curiosity and challenge

For centuries, scholars and scientists have defined the “good life” in one of two ways: a life that is rooted in happiness, characterized by positive emotions, or one that is centered on meaning, guided by purpose and personal fulfillment. But what if there is another, equally valuable path — one that prioritizes challenge, change and curiosity? “We found that what was missing was psychological richness — experiences that challenge you, change your perspective and satisfy your curiosity.” — Erin Westgate, Ph.D., assistant professor psychology, director of the Florida Social Cognition and Emotion Lab This third dimension, which may result in a more psychologically rich life for some, is being explored in a new study — led by University of Florida psychologist Erin Westgate, Ph.D., in collaboration with Shigehiro Oishi, Ph.D., of the University of Chicago. According to their research, some people prioritize variety, novelty and intellectually stimulating experiences, even when those experiences are difficult, unpleasant or lack clear meaning. “This idea came from the question: Why do some people feel unfulfilled even when they have happy and meaningful lives?” Westgate said. “We found that what was missing was psychological richness — experiences that challenge you, change your perspective and satisfy your curiosity.” Westgate and Oishi’s research shows that a psychologically rich life is distinct from lives defined by happiness or meaning. While happiness focuses on feeling good, and meaning is about doing good, richness is about thinking deeply and seeing the world differently. And for a significant minority of people around the world, that third path is the one they would choose — even if it means giving up happiness or meaning. A new way to think about the ‘good life’ According to Westgate and Oishi, psychological richness is defined as a life filled with diverse, perspective-changing experiences — whether these are external, such as traveling or undertaking new challenges, or internal, like absorbing powerful books or pieces of music. “A psychologically rich life can come from something as simple as reading a great novel or hearing a haunting song,” Westgate said. “It doesn’t have to be about dramatic events, but it can shift the way you see the world.” Unlike happy or meaningful experiences, rich experiences are not always pleasant or purposeful. “College is a good example. It’s not always fun, and you might not always feel a deep sense of meaning, but it changes how you think,” Westgate said. “The same goes for experiences like living through a hurricane. You wouldn’t call it happy or even meaningful, but it shakes up your perspective.” Researchers in Westgate’s lab at UF have been studying how people respond to events like hurricanes, tracking students’ emotions and reactions as storms approach. The results show that many people have viewed these challenging experiences as psychologically rich — altering how they saw the world, even if they didn’t enjoy them. The roots of the idea While the study is new, the concept has been years in the making. Westgate and Oishi first introduced the term “psychologically rich life” in 2022, building on earlier research and scale development around 2015. Their latest paper expands the idea, showing that the concept resonates with people across cultures and fills a gap in how people define well-being. “In psychology and philosophy, dating back to Aristotle, there’s been a focus on hedonic versus eudaimonic well-being — happiness versus meaning,” Westgate said. “What we’re doing is saying, there’s another path that’s just as important. And for some people, it’s the one they value most.” While many people ideally want all three — happiness, meaning and richness — there are trade-offs. Rich experiences often come at the cost of comfort or clarity. “Interesting experiences aren’t always pleasant experiences,” Westgate said. “But they’re the ones that help us grow and see the world in new ways.” Westgate hopes the study will broaden how psychologists and the public think about what it means to live well. “We’re not saying happiness and meaning aren’t important,” Westgate said. “They are. But we’re also saying don’t forget about richness. Some of the most important experiences in life are the ones that challenge us, that surprise us and that make us see the world differently.”

February 16, 2026

3 min

‘Love Island’ isn’t real, but it might reflect the way we date

For millions of viewers, “Love Island” has been a summer obsession – a chance to peek in on a sunny villa full of beautiful singles looking for love. But according to Andrew Selepak, Ph.D., a media professor at the University of Florida, the reality show isn’t really about romance. “The reality of reality TV is that it doesn’t reflect reality,” Selepak said. “These are people who were selected; they were cast just like you would cast a movie or a scripted TV show.” Still, what happens on the island isn’t completely disconnected from real life. The show's format, which is built on snap decisions, physical attraction, and frequent recouplings, mirrors the current dating landscape in unsettling ways. “I think it's reflective of the current culture that young people are experiencing with dating, which is very superficial and doesn't lead to long-term lasting relationships because a long-term lasting relationship can't be based on superficial qualities,” Selepak said. Selepak compares “Love Island” to “TV Tinder.” Much like on dating apps, contestants size each other up based on looks and vibes rather than values or long-term compatibility. And while the show promotes the idea of finding “the one,” the numbers tell a different story. “It’s like less than 12% of the couples actually remain together for any period of time,” Selepak said. “At some point, you would think people would realize it’s fake.” However, viewers continue to watch, and contestants continue to sign up. Why? Because the point isn't necessarily to find love. It's about visibility, likes and followers. “This is where you have the social media aspect playing in, where people are looking to become influencers and to gain fame, notoriety, likes and follows,” Selepak said. “The people who are on the shows, these are people who intentionally have gone out and said, 'I want my dirty laundry to be on TV.’ There's a narcissistic aspect of wanting to be on a show like that. Most people, I think, would be hesitant to tell their deep, dark secrets – or tell the things about themselves that they would normally only share with a select few – to a large audience.” For contestants, this often means performing love rather than experiencing it – a behavior that echoes real-world dating on social media. For audiences, “Love Island” gives them the dissatisfaction of watching beautiful people experience the same dating struggles they do. In the end, “Love Island” may not teach us how to find lasting love, but it might explain why so many people are struggling to.

February 12, 2026

2 min

Scientist’s cat, again, helps discover new virus

Pepper, the pet cat who made headlines last year for his role in the discovery of the first jeilongvirus found in the U.S., is at it again. This time, his hunting prowess contributed to the identification of a new strain of orthoreovirus. John Lednicky, Ph.D., Pepper’s owner and a University of Florida College of Public Health and Health Professions virologist, took Pepper’s catch — a dead Everglades short-tailed shrew — into the lab for testing as part of his ongoing work to understand transmission of the mule deerpox virus. Testing revealed the shrew had a previously unidentified strain of orthoreovirus. Viruses in this genus are known to infect humans, white-tailed deer, bats and other mammals. While orthoreoviruses’ effects on humans are not yet well understood, there have been rare reports of the virus being associated with cases of encephalitis, meningitis and gastroenteritis in children. “The bottom line is we need to pay attention to orthoreoviruses, and know how to rapidly detect them,” said Lednicky, a research professor in the PHHP Department of Environmental and Global Health and a member of UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute. The UF team published the complete genomic coding sequences for the virus they named “Gainesville shrew mammalian orthoreovirus type 3 strain UF-1” in the journal Microbiology Resource Announcements. “There are many different mammalian orthoreoviruses and not enough is known about this recently identified virus to be concerned,” said the paper’s lead author Emily DeRuyter, a UF Ph.D. candidate in One Health. “Mammalian orthoreoviruses were originally considered to be ‘orphan’ viruses, present in mammals including humans, but not associated with diseases. More recently, they have been implicated in respiratory, central nervous system and gastrointestinal diseases.” The Lednicky lab’s jeilongvirus and orthoreovirus discoveries come on the heels of the team publishing their discovery of two other novel viruses found in farmed white-tailed deer. Given the propensity of viruses to constantly evolve, paired with the team’s sophisticated lab techniques, finding new viruses isn’t entirely surprising, Lednicky said. “I’m not the first one to say this, but essentially, if you look, you’ll find, and that’s why we keep finding all these new viruses,” Lednicky said. Like influenza virus, two different types of orthoreovirus can infect a host cell, causing the viruses’ genes to mix and match, in essence, creating a brand new virus, Lednicky said. In 2019, Lednicky and colleagues isolated the first orthoreovirus found in a deer. That strain’s genes were nearly identical to an orthoreovirus found in farmed mink in China and a deathly ill lion in Japan. How in the world, the scientific community wondered, could the same hybrid virus appear in a farmed deer in Florida and two species of carnivores across the globe? Some experts speculated that components of the animals’ feed could have come from the same manufacturer. With so many unanswered questions about orthoreoviruses and their modes of transmission, prevalence in human and animal hosts and just how sick they could make us, more research is needed, DeRuyter and Lednicky said. Next steps would include serology and immunology studies to understand the threat Gainesville shrew mammalian orthoreovirus type 3 strain UF-1 may hold for humans, wildlife and pets. For readers concerned about Pepper’s health, rest assured. He has shown no signs of illness from his outdoor adventures and will likely continue to contribute to scientific discovery through specimen collection. “This was an opportunistic study,” Lednicky said. “If you come across a dead animal, why not test it instead of just burying it? There is a lot of information that can be gained.”

February 11, 2026

3 min

New study suggests Florida Chagas disease transmission

Researchers from the University of Florida Emerging Pathogens Institute and Texas A&M University gathered their resources to investigate the potential of vector-borne transmission of Chagas in Florida. The 10-year-long study, published in the Public Library of Science Neglected Tropical Diseases, used data from Florida-based submissions, as well as field evidence collected from 23 counties across Florida. Chagas disease is considered rare in the United States. Since it is not notifiable to most state health departments, it is quite difficult to know exactly how many cases there are and how frequently it’s transmitted. Chagas disease is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Nuisance blood-sucking insects known as kissing bugs spread the parasite to humans when exposure to their feces penetrates the mucus membranes, breaches the skin or gets orally ingested. Interestingly, it is believed that most companion animals, like dogs and cats, acquire the parasite from eating the kissing bug itself. The first record of kissing bugs, scientifically known as Triatoma sanguisuga, harboring T. cruzi in Florida was from an insect in Gainesville in 1988. However, kissing bugs have been calling the state home for far longer than humans have. Currently, there are two known endemic species of kissing bugs in the Sunshine State: Triatoma sanguisuga, the species invading homes, and the cryptic species Paratriatoma lecticularia, which live primarily in certain Floridan ecosystems but were not found in this study. Read more ...

February 07, 2026

1 min